Supply@ME Capital: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 649: | Line 649: | ||

== What are the key risks of investing in the company? == | == What are the key risks of investing in the company? == | ||

As with any investment, investing in Supply@ME Capital carries a level of risk. The key risks can be found below. Overall, based on the Supply@ME Capital's market beta (i.e. 8.89)<ref>Research shows that an investment has two main types of risks: 1) non-systematic and 2) systematic. Systematic risk is the risk related to the overall market, and non-systematic risk is the risk that's specific to an individual investment. Evidence shows that taking on non-systematic risk is inefficient, and it's, therefore, best to eliminate it; and in most cases, elimination is fairy easy to do [by holding a diversified portfolio of investments (i.e. around 15 investments)]. Accordingly, when assessing the riskiness of an investment, it’s best to look at the systematic risk only (i.e. ignore the non-systematic risk). A key measure of systematic risk is beta, and a main way to determine the riskiness of an investment is to compare the beta of the investment with the beta of the market, which is 1. For example, Supply@ME Capital's beta is 8.89, and is, accordingly, 989% above the market beta (of 1); assuming that a 'high' level of riskiness is 50% or more above the market beta, then the riskiness of investing in | As with any investment, investing in Supply@ME Capital carries a level of risk. The key risks can be found below. Overall, based on the Supply@ME Capital's market beta (i.e. 8.89)<ref>Research shows that an investment has two main types of risks: 1) non-systematic and 2) systematic. Systematic risk is the risk related to the overall market, and non-systematic risk is the risk that's specific to an individual investment. Evidence shows that taking on non-systematic risk is inefficient, and it's, therefore, best to eliminate it; and in most cases, elimination is fairy easy to do [by holding a diversified portfolio of investments (i.e. around 15 investments)]. Accordingly, when assessing the riskiness of an investment, it’s best to look at the systematic risk only (i.e. ignore the non-systematic risk). A key measure of systematic risk is beta, and a main way to determine the riskiness of an investment is to compare the beta of the investment with the beta of the market, which is 1. For example, Supply@ME Capital's beta is 8.89, and is, accordingly, 989% above the market beta (of 1); assuming that a 'high' level of riskiness is 50% or more above the market beta, then the riskiness of investing in Supply@ME Captial is considered to be 'high' (989%>50%).</ref>, the degree of risk associated with an investment in Supply@ME Capital is 'high'. | ||

=== Risk factors specific and material to the group === | === Risk factors specific and material to the group === | ||

| Line 810: | Line 810: | ||

|In regards to the growth-adjusted EV/sales multiple, for the sales figure, which year to you want to use? | |In regards to the growth-adjusted EV/sales multiple, for the sales figure, which year to you want to use? | ||

|Year | |Year 1 | ||

| | |Research suggests that when using the relative valuation approach, it's best to use a time period of 12 months or less. Accordingly, for the sales figure, we suggest using Year 1. | ||

|- | |- | ||

|In regards to the growth-adjusted EV/sales multiple, for the sales growth figure, which year(s) do you want to use? | |In regards to the growth-adjusted EV/sales multiple, for the sales growth figure, which year(s) do you want to use? | ||

|Year | |Year 2 to 4, from now | ||

|We suggest that for the sales growth figure, it's best to use Year | |We suggest that for the sales growth figure, it's best to use Year 2 to 4. | ||

|- | |- | ||

|In regards to the growth-adjusted EV/sales multiple, what multiple figure do you want to use? | |In regards to the growth-adjusted EV/sales multiple, what multiple figure do you want to use? | ||

| | |100x | ||

|In our view, Supply@ME Capital's closest peer is [[Apple, Inc.|Apple, Inc]]. [[Apple, Inc.|Apple, Inc]] trades on a multiple of | |In our view, Supply@ME Capital's closest peer is [[Apple, Inc.|Apple, Inc]]. [[Apple, Inc.|Apple, Inc]] trades on a multiple of 100x. | ||

|- | |- | ||

|Which financial forecasts to use? | |Which financial forecasts to use? | ||

| Line 833: | Line 830: | ||

|- | |- | ||

|Which time period do you want to use to estimate the expected return? | |Which time period do you want to use to estimate the expected return? | ||

|Between now and | |Between now and one year time | ||

| | |Research suggests that when using the relative valuation approach, it's best to estimate the expected return of the company between now and one year time. | ||

|} | |} | ||

=== Sensitive analysis === | === Sensitive analysis === | ||

The two main inputs that result in the greatest change in the expected return of the | The two main inputs that result in the greatest change in the expected return of the Supply@ME Capital investment are, in order of importance (from highest to lowest): | ||

#The | #The growth-adjusted EV/sales multiple (the default multiple is 50x); and | ||

#The Year- | #The Year-one sales forecast (the default forecast is $1 million); and | ||

#The Year 2 to 4 sales growth forecast (the default forecast is 300%) | |||

The impact of a 10% change in those main inputs to the expected return of the | The impact of a 10% change in those main inputs to the expected return of the Supply@ME Capital investment is shown in the table below. | ||

{| class="wikitable sortable" | {| class="wikitable sortable" | ||

| Line 852: | Line 850: | ||

!10% better | !10% better | ||

|- | |- | ||

|The | |The growth-adjusted EV/sales multiple | ||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |||

|The Year-one sales forecast | |||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

|The Year | |The Year 2 to Year 4 sales growth forecast | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

Revision as of 23:03, 26 November 2022

Supply@ME Capital plc operates a platform that provides inventory monetisation services to manufacturing and trading companies in the United Kingdom, the Middle East, Italy, North Africa, the United States, and internationally. The company is based in London, the United Kingdom.

Operations

How did the idea of the company come about?

What's the mission of the company?

What's the company's main offering(s)?

Who’s the target audience of the company’s flagship/first product?

The audience is small and medium-sized, manufacturing companies (i.e. companies that hold a large amount of inventory), such as (Apple, Inc). Note, here, inventory refers to the goods and materials that a business holds for the ultimate goal of resale, production or utilisation.

Most companies hold some amount of inventory. Which companies in particular? I suggest targeting companies that hold a large amount of inventory. For me, it makes sense to sell the unwanted inventory (or any inventory for that matter) back to the place/company that the inventory was bought.

What's a major problem that the target audience experience?

The problem is that holding inventory costs money, mainly in terms of 1) acquiring the inventory in the first place and 2) then storing the inventory until its eventual use and 3) depreciation (most inventory depreciates over time).

What's a key solution to the problem/what's the product?

The solution is xxx.

xxx is a platform that is designed to enable manufacturing companies to sell its unwanted inventory faster than ever, allowing the company to maximise its profits.

What makes the platform unique is that it's the only platform that xxx.

What makes the product unique?

Which are the main competitors of the product?

| Supply@ME | TraxPay | Demica | Hitachi Capital (UK) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Price | ||||

What is the main way that the product expects to make money?

What’s the size of the company target market?

Total Addressable Market

Here, the total addressable market (TAM) is defined as the global automotive market, and based on a number of assumptions, it is estimated that the size of the market as of today (30th May 2022), in terms of revenue, is $3.0 trillion.

It can be strongly argued that given the company's mission, the total addressable market is actually the global energy market; and research suggests that the estimated size of that market is $6.1 trillion.[1]

Serviceable Available Market

Here, the serviceable available market (SAM) is defined as the global car market, and based on a number of assumptions, it is estimated that the size of the market as of today (30th May 2022), in terms of revenue, is $1.0 trillion.

Serviceable Obtainable Market

Here, the serviceable obtainable market (SOM) is defined as the US car market, and based on a number of assumptions, it is estimated that the size of the market as of today (30th May 2022), in terms of revenue, is $262 billion.

What's the biggest achievement of the company?

What's the next key milestone of the company?

Who are the key members of the team?

Directors

Alessandro Zamboni – Chief Executive Officer and Executive Director

Alessandro is a director who specialises in the financial services industry and related strategic and digital models. Since 2008, he has been managing the delivery and the sales operations of a consulting company specialising in Regulatory & Internal Controls for Banks and Insurance Firms. He founded TAG, the former parent company of Supply@ME S.r.l., in 2014. He holds a BA degree in Economics from the University of Turin.

Albert Ganyushin – Independent Chairperson and Non-Executive Director

Albert was appointed as independent chairperson and a Non-Executive Director in 2022 following a long career in capital markets. Since 2017, he has served as Head of Capital Markets at Dr. Peters Group with responsibility for international institutional business, including investment management, capital markets, financing and investor relations. Prior to joining Dr. Peters Group, between 2010 and 2016, he worked in leadership roles in the listings business of NYSE Euronext Group after a career in investment banking that started with Deutsche Bank A.G. (London Branch) in 2000. He graduated with an MBA degree from London Business School in 2000 and began his professional career as a management consultant with Accenture in London in 1995.

Enrico Camerinelli – Independent Non-Executive Director

Mr. Camerinelli keeps abreast of market trends and business practices by taking an active part in projects launched by the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, the World Bank, the World Trade Board, and the Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals. He regularly attends major industry events as invited guest speaker and writes on specialized magazines and papers. He holds an MSc in Electronic Engineering from Università degli Studi "La Sapienza", Rome, Italy.

David Bull – Independent Non-Executive Director

Mr. Bull, a Chartered Accountant, is a technology-driven experienced financial services professional with a banking and financial services digitisation mindset. He has held a number of senior board roles within banking, asset finance, treasury and credit management institutions, including several years as Chief Financial Accountant at The Bank of England, and is currently non-executive director of Epsion Capital Limited, an independent corporate advisory firm based in London. He holds a BSc (First Class) in Mathematics and Statistics from the University of Bradford.

Andrew Thomas – Independent Non-Executive Director

Andrew has over 20 years' experience in various business advisory roles and during this time has worked across the US, UK, EU and APAC regions, acquiring expertise of onshore and offshore fund structuring and oversight, particularly in relation to regulatory issues. He also has extensive experience in mitigating ESG risks while helping organisations to maximise ESG opportunities. He holds BA in History and Politics from the University of Exeter.

Dr. Thomas (Tom) James – Executive Director

Tom is an Executive Director, and the CIO, CEO and co-founder of the Trade Flow Funds and FinTech solutions. He has over 30 years of commercial expertise in the commodity and energy industry and is the business and system architect for this unique and innovative digitised trade finance solution for bulk physical commodity transactions. He has experience of senior regulated roles in financial institutions (including Bank of Tokyo Mitsubishi UFJ, Credit Agricole and Credit Lyonnais) and various trading firms including BHP Billiton, covering a full range of functional areas including trade finance, project finance, investment banking, supply chain/operations, derivatives, physical markets, and fund management. During his career he has operated in many countries in Africa, Europe, Middle East, and Asia Pacific. He has authored over nine books in the energy and commodity trading and risk management field and served as Chair Professor and Adjunct Professor at various universities around the world and is a former member of the United Nations FAO Commodity Risk Management Advisory Group, and a former Senior Energy Advisor to the United States Department of Defense (TFBSO). He holds a PhD in Practices for the Global Commodity Markets within the Functional Disciplines of Trading and Risk Management and a Masters in Energy Price Risk Management from Middlesex University London.

John Collis – Executive Director

John is an Executive Director, and is co-founder of the Trade Flow Funds and FinTech solution where he holds the position of Chief Risk Officer (CRO). As well as overseeing the development of the fund’s critical legal infrastructure and working with leading counsel on its enforceability, John has overseen the classification of the specialist intellectual property developed and acquired by TradeFlow and its licensing. John is a commercial lawyer with expertise in regulatory, compliance, structuring, and transactional matters. John operated his own law firm from 2003, specialising in international commercial work. John has written and lectured about the rule of law, Eurasia Economic Union, CSTO, and International Commercial Enforcement. Before becoming a lawyer, John worked for Ernst & Young, he was educated at Oxford University and is chairman of Hertford College RFC.

Senior management

Amy Benning – Chief Financial Officer

Amy gained Chartered Accountancy qualifications in New Zealand while working with KPMG on a range of clients across various industry sectors. On moving to the United Kingdom, Amy worked briefly with BP’s shipping arm, before moving to PwC’s London Capital Markets Team where she spent 12 years focusing on technical accounting, mergers and acquisitions and initial public offerings for a wide range of clients. In 2018, Amy moved to Alfa Financial Software Holdings plc, a developer and provider of software for the automotive leasing sector company with ordinary shares admitted to a Premium Listing and to trading on the Main Market. As Finance Director, Amy was responsible for the team managing accounting, reporting (internal & external), corporate governance, audit, systems, process improvement, controls and transactional accounting. Amy joined the Group in June 2021. She holds a BCA in Accountancy, a BSc in Genetics, Biochemistry and Molecular Biology and a post-graduate diploma in Professional Accounting from Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand.

Stuart Nelson – Group Head of Enterprise Risk Management

Stuart is an experienced credit risk analyst, with global experience of assessing the risk of financing solutions across multiple asset classes. Having begun his career at JPMorgan in the EMEA Emerging Markets Team in 2000, he then spent almost two decades in leadership roles at S&P Global Ratings. During his time at S&P, he managed multiple teams across the European office network in London, Milan, Frankfurt, Madrid and Paris, focusing on the assessment of asset securitisation in all sectors, with oversight of ratings on securities of more than €50 billion equivalent over that period. From 2015, he concentrated his attention on the refinement and validation of risk methodologies across a global spectrum of asset classes. He joined the Group in 2020, where he currently monitors all aspects of the risk and operational functions. He holds a Masters in History from the University of Cambridge.

Alice Buxton – Chief People Officer

Alice is a human resources leader motivated to help businesses succeed by creating environments which enable individuals, teams and leaders to thrive. She has considerable experience in the Financial Services and FinTech industries. Most recently she built the Global Talent function at Greensill, helping the business grow its workforce from approx. 250 to over 1200 in multiple jurisdictions in just over 2 years. Previously she worked as an Executive Director in Goldman Sachs Human Capital Management Division, focusing on the EMEA Trading floor and Risk, Audit and Compliance teams attracting and developing high potential talent. Before this she worked in Talent Acquisition for Ernst and Young’s London office, recruiting for their risk and advisory business. Alice holds a BSc in Psychology, MSc in Human Resource Management and is a qualified corporate and executive coach.

Mark Kavanagh – Group Head of Operations and Transformation

Mark is an experienced Risk Leader with over 25 years in Credit & Risk functions. Before joining the Group, Mark worked for Greensill Capital as Head of Product Risk. Whilst there, he implemented Accounts Receivable policies and procedures, installed an AR platform, helped Greensill Capital expand territorially, and trained the Credit team on any new product offerings, acquisitions and integrations. Prior to that, he worked for GE Working Capital Solutions (the monetisation arm of General Electric group) for 15 years, heading up their European Credit Team, managing the auto scoring and decisioning system, and ensuring processes were safe and efficient.

Nicola Bonini – Group Head of Origination

Nicola has more than 20 years' experience in balance sheet lending and cashflow finance, gained during her time at some of the UK’s most prominent banking institutions. Previously, she was Vice President and Head of Commercial Finance at Bank Leumi (UK) plc, where she managed a portfolio of companies with turnover of up to £1bn. Before this, Nicola served as Executive Director at Falcon Group UK, where she joined the newly formed UK inventory finance team. Nicola has also held senior, highprofile business development and relationship management roles at major banks, including BNP Paribas, The Royal Bank of Scotland and Bank of Scotland Corporate. Nicola joined the Group in September 2021 to take a leading role in business development, client onboarding and retention. She holds a BA in Business Studies from the University of East London.

How much does the company expect to make over the next five years?

Historic

Most recent quarter

During the three months ended 31st March 2022, net income increased to $3.32 billion on revenues of $18.76 billion, representing a respective increase of 7x and 81% compared to the prior year, and equating to a net income margin of 18%. The company ended the quarter with cash of $18.01 billion, representing an increase of 2% from the end of 2021.

Most recent year

For the fiscal (and calendar) year 2021, Supply@ME Capital reported a net income of $5.52 billion.[2] The annual revenue was $53.8 billion, an increase of 71% over the previous fiscal year.[2]

The Company is of the opinion that the group has sufficient working capital for its present requirements, that is, for at least 12 months from the date of its recent prospectus (i.e. 3rd October 2022).

All periods

| Year | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year end date | 31/12/2005 | 31/12/2006[4][5] | 31/12/2007 | 31/12/2008 | 31/12/2009 | 31/12/2010[5] | 31/12/2011[5] | 31/12/2012[5] | 31/12/2013[5] | 31/12/2014[5] | 31/12/2015[5] | 31/12/2016[5] | 31/12/2017[5] | 31/12/2018[5] | 31/12/2019[5] | 31/12/2020[5] | 31/12/2021[5] |

Income statement

| |||||||||||||||||

| Revenues ($'million) | 0 | 0 | 0.073 | 15 | 112 | 117 | 204 | 413 | 2,013 | 3,198 | 4,046 | 7,000 | 11,759 | 21,461 | 24,578 | 31,536 | 53,823 |

| Net profits ($'million) | -12 | -30 | -78 | -83 | −56 | −154 | −254 | −396 | −74 | −294 | −889 | −675 | −1,962 | −976 | −862 | 721 | 5,519 |

Balance sheet

| |||||||||||||||||

| Total assets ($'million) |

8 | 44 | 34 | 52 | 130 | 386 | 713 | 1,114 | 2,417 | 5,831 | 8,068 | 22,664 | 28,655 | 29,740 | 34,309 | 52,148 | 62,131 |

Other

| |||||||||||||||||

| Employees | NA | 70 | 268 | 252 | 514 | 899 | 1,417 | 2,914 | 5,859 | 10,161 | 13,058 | 17,782 | 37,543 | 48,817 | 48,016 | 70,757 | 99,290 |

Forward

What are the financial forecasts?

| Year | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 38 | 39 | 40 | 41 | 42 | 43 | 44 | 45 | 46 | 47 | 48 | 49 | 50 | 51 | 52 | 53 | 54 | 55 | 56 | 57 | 58 | 59 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year end date | 31/12/2022 | 31/12/2023 | 31/12/2024 | 31/12/2025 | 31/12/2026 | 31/12/2027 | 31/12/2028 | 31/12/2029 | 31/12/2030 | 31/12/2031 | 31/12/2032 | 31/12/2033 | 31/12/2034 | 31/12/2035 | 31/12/2036 | 31/12/2037 | 31/12/2038 | 31/12/2039 | 31/12/2040 | 31/12/2041 | 31/12/2042 | 31/12/2043 | 31/12/2044 | 31/12/2045 | 31/12/2046 | 31/12/2047 | 31/12/2048 | 31/12/2049 | 31/12/2050 | 31/12/2051 | 31/12/2052 | 31/12/2053 | 31/12/2054 | 31/12/2055 | 31/12/2056 | 31/12/2057 | 31/12/2058 | 31/12/2059 | 31/12/2060 | 31/12/2061 | 31/12/2062 | 31/12/2063 |

Income statement

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Revenues ($'million) | $78,935 | $112,257 | $154,816 | $207,049 | $268,527 | $337,721 | $411,894 | $487,157 | $558,739 | $621,448 | $670,282 | $701,078 | $711,102 | $699,445 | $667,163 | $617,116 | $553,551 | $481,510 | $406,171 | $332,253 | $263,564 | $202,749 | $151,247 | $109,414 | $76,757 | $52,217 | $34,448 | $22,038 | $13,673 | $8,226 | $4,799 | $2,715 | $1,490 | $793 | $409 | $205 | $99 | $47 | $21 | $9 | $4 | $2 |

| Gross profits ($'million) | $23,680 | $33,677 | $46,445 | $62,115 | $80,558 | $101,316 | $185,352 | $219,221 | $251,432 | $279,652 | $301,627 | $315,485 | $319,996 | $314,750 | $300,223 | $277,702 | $249,098 | $216,679 | $182,777 | $149,514 | $118,604 | $91,237 | $68,061 | $49,236 | $34,541 | $23,498 | $15,502 | $9,917 | $6,153 | $3,702 | $2,160 | $1,222 | $670 | $357 | $184 | $92 | $45 | $21 | $10 | $4 | $2 | $1 |

| Operating profits ($'million) | $11,840 | $16,839 | $23,222 | $31,057 | $40,279 | $50,658 | $123,568 | $146,147 | $167,622 | $186,434 | $201,085 | $210,323 | $213,331 | $209,834 | $200,149 | $185,135 | $166,065 | $144,453 | $121,851 | $99,676 | $79,069 | $60,825 | $45,374 | $32,824 | $23,027 | $15,665 | $10,335 | $6,612 | $4,102 | $2,468 | $1,440 | $815 | $447 | $238 | $123 | $61 | $30 | $14 | $6 | $3 | $1 | $1 |

| Net profits ($'million) | $9,354 | $13,302 | $18,346 | $24,535 | $31,820 | $40,020 | $97,619 | $115,456 | $132,421 | $147,283 | $158,857 | $166,156 | $168,531 | $165,769 | $158,118 | $146,256 | $131,192 | $114,118 | $96,263 | $78,744 | $62,465 | $48,052 | $35,846 | $25,931 | $18,191 | $12,376 | $8,164 | $5,223 | $3,240 | $1,949 | $1,137 | $643 | $353 | $188 | $97 | $48 | $24 | $11 | $5 | $2 | $1 | $0 |

What are the assumptions used to estimate the financial forecasts?

| Description | Value | Commentary |

|---|---|---|

Revenue

| ||

| What's the estimated current size of the total addressable market? | $2,975,000,000 | Here, the total addressable market (TAM) is defined as the global automotive market, and based on a number of assumptions[Note 2], it is estimated that the size of the market as of today (30th May 2022), in terms of revenue, is $2.975 trillion.

|

| What is the estimated company lifespan? | 60 years | Supply@ME Capital employs around 110,000, making the company a large organisation (more than 10,000 employees), and research shows that the average lifespan of a large corporation is around 50 years.[7] |

| What's the estimated annual growth rate of the total addressable market over the lifecycle of the company? | 3% | Research shows that the growth rate of the global automotive market (i.e. the total addressable market) is similar to the growth rate of global gross domestic product[8], which has averaged (medium) around 3% per year in the last 20 years (2001 to 2022)[9]. |

| What's the estimated company peak market share? | 10% | We estimate that especially given the leadership of the company, the peak market share of Supply@ME Capital is around 10%, and, therefore, suggests using the share amount here. As of 31st December 2021, Supply@ME Capital's current share of the market is estimated at around 1.8%. |

| Which distribution function do you want to use to estimate company revenue? | Gaussian | Research suggests that the revenue pattern of companies is similar to the pattern produced by the Gaussian distribution function (i.e. the revenue distribution is bell shaped)[10], so we suggest using that function here. |

| What's the estimated standard deviation of company revenue? | 6 years | Another way of asking this question is this way: within how many years either side of the mean does 68% of revenue occur? Based on Supply@ME Capital's current revenue amount (i.e. $54 billion) and Supply@ME Capital's estimated lifespan (i.e. 60 years) and Supply@ME Capital's estimated current stage of its lifecycle (i.e. growth stage), the we suggest using 6 years (i.e. 68% of all sales happen within 6 years either side of the mean year), so that's what's used here. |

Growth stages

| ||

| How many main stages of growth is the company expected to go through? | 4 stages | Research suggests that a company typically goes through four distinct stages of cash flow growth.[11] Research also shows that incorporating those stages into the discounted cash flow model improves the quality of the model and, ultimately, the quality of the value estimation.[12]

In addition, research shows that a key way to determine the stage which a company is in is by examining the cash flow patterns of the company.[13] A summary of the economic links to cash flow patterns can be found in the appendix of this report. We estimate that with Supply@ME Capital's operating cash flows positive (+), investing cash flows negative (-) and its financing cash flows positive (+), the company is in the second stage of growth (i.e. the 'growth' stage), and, therefore, it has a total of three main stages of growth. Note, to account for one-off events, the three-year average (median) amount was used to calculate the cash flows. |

| What proportion of the company lifecycle is represented by growth stage 1? | 30% | Research suggests 30%.[14] |

| What proportion of the company lifecycle is represented by growth stage 2? | 10% | Research suggests 10%.[14] |

| What proportion of the company lifecycle is represented by growth stage 3? | 20% | Research suggests 20%.[14] |

| What proportion of the company lifecycle is represented by growth stage 4? | 40% | Research suggests 40%.[14] |

Growth stage 2

| ||

| Cost of goods sold as a proportion of revenue (%) | 79% | Research suggests that it's best to use a similar margin rate as the one used by peers that are in the same growth stage (i.e. growth stage 2)[15], and the margin for its peers is 79%. Information on the peers and the calculation of the figure used here can be found in the appendix of this report. |

| Operating expenses as a proportion of revenue (%) | 15% | Research suggests that it's best to use a similar margin rate as the one used by peers that are in the same growth stage (i.e. growth stage 2)[15], and the margin for its peers is 15%. Information on the peers and the calculation of the figure used here can be found in the appendix of this report. |

| Tax rate (%) | 11% | Research suggests that it's best to use a similar rate as the one used by peers that are in the same growth stage (i.e. growth stage 2)[15], and the rate for its peers is 11%. |

| Depreciation and amortisation as a proportion of revenue (%) | 7% | Research suggests that it's best to use a similar margin rate as the one used by peers that are in the same growth stage (i.e. growth stage 2)[15], and the margin for its peers is 7%. Information on the peers and the calculation of the figure used here can be found in the appendix of this report. |

| Fixed capital as a proportion of revenue (%) | 10% | Research suggests that it's best to use a similar amount as the one used by peers that are in the same growth stage (i.e. growth stage 2)[15], and the amount for its peers is 10%. Information on the peers and the calculation of the figure used here can be found in the appendix of this report. |

| Working capital as a proportion of revenue (%) | 15% | Research suggests that it's best to use a similar amount as the one used by peers that are in the same growth stage (i.e. growth stage 2)[15], and the amount for its peers is 15%. |

| Net borrowing ($000) | Zero | We suggest that for simplicity, the net borrowing figure is zero. |

| Interest amount ($000) | Zero | We suggest that for simplicity, the interest amount figure is zero. |

Growth stage 3

| ||

| Cost of goods sold as a proportion of revenue (%) | 62% | Research suggests that it's best to use a similar margin rate as the one used by peers that are in the same growth stage (i.e. growth stage 3)[15], and the margin for its peers is 62%. Information on the peers and the calculation of the figure used here can be found in the appendix of this report. |

| Operating expenses as a proportion of revenue (%) | 13% | Research suggests that it's best to use a similar margin rate as the one used by peers that are in the same growth stage (i.e. growth stage 3)[15], and the margin for its peers is 13%. Information on the peers and the calculation of the figure used here can be found in the appendix of this report. |

| Tax rate (%) | 14% | Research suggests that it's best to use a similar rate as the one used by peers that are in the same growth stage (i.e. growth stage 3)[15], and the rate for its peers is 14%. Information on the peers and the calculation of the figure used here can be found in the appendix of this report. |

| Depreciation and amortisation as a proportion of revenue (%) | 4% | Research suggests that it's best to use a similar amount as the one used by peers that are in the same growth stage (i.e. growth stage 3)[15], and the amount for its peers is 4%. Information on the peers and the calculation of the figure used here can be found in the appendix of this report. |

| Fixed capital as a proportion of revenue (%) | 3% | Research suggests that it's best to use a similar amount as the one used by peers that are in the same growth stage (i.e. growth stage 3)[15], and the amount for its peers is 3%. Information on the peers and the calculation of the figure used here can be found in the appendix of this report. |

| Working capital as a proportion of revenue (%) | 10% | Research suggests that it's best to use a similar amount as the one used by peers that are in the same growth stage (i.e. growth stage 4)[15], and the amount for its peers is 10%. Information on the peers and the calculation of the figure used here can be found in the appendix of this report. |

| Net borrowing ($000) | Zero | We suggest that for simplicity, the net borrowing figure is zero. |

| Interest amount ($000) | Zero | We suggest that for simplicity, the interest amount figure is zero. |

Growth stage 4

| ||

| Cost of goods sold as a proportion of revenue (%) | 99% | Research suggests that it's best to use a similar margin rate as the one used by peers that are in the same growth stage (i.e. growth stage 4)[15], and the margin for its peers is 99%. Information on the peers and the calculation of the figure used here can be found in the appendix of this report. |

| Operating expenses as a proportion of revenue (%) | 15% | Research suggests that it's best to use a similar margin rate as the one used by peers that are in the same growth stage (i.e. growth stage 4)[15], and the margin for its peers is 15%. Information on the peers and the calculation of the figure used here can be found in the appendix of this report. |

| Tax rate (%) | 0% | Research suggests that it's best to use a similar rate as the one used by peers that are in the same growth stage (i.e. growth stage 4)[15], and the rate for its peers is 0%. Information on the peers and the calculation of the figure used here can be found in the appendix of this report. |

| Depreciation and amortisation as a proportion of revenue (%) | 37% | Research suggests that it's best to use a similar amount as the one used by peers that are in the same growth stage (i.e. growth stage 4)[15], and the amount for its peers is 37%. Information on the peers and the calculation of the figure used here can be found in the appendix of this report. |

| Fixed capital as a proportion of revenue (%) | 1% | Research suggests that it's best to use a similar amount as the one used by peers that are in the same growth stage (i.e. growth stage 4)[15], and the amount for its peers is 1%. Information on the peers and the calculation of the figure used here can be found in the appendix of this report. |

| Working capital as a proportion of revenue (%) | 10% | Research suggests that it's best to use a similar amount as the one used by peers that are in the same growth stage (i.e. growth stage 4)[15], and the amount for its peers is 10%. Information on the peers and the calculation of the figure used here can be found in the appendix of this report. |

| Net borrowing ($000) | Zero | We suggest that for simplicity, the net borrowing figure is zero. |

| Interest amount ($000) | Zero | We suggest that for simplicity, the interest amount figure is zero. |

What are the key risks of investing in the company?

As with any investment, investing in Supply@ME Capital carries a level of risk. The key risks can be found below. Overall, based on the Supply@ME Capital's market beta (i.e. 8.89)[16], the degree of risk associated with an investment in Supply@ME Capital is 'high'.

Risk factors specific and material to the group

- The group is at the early stage of its development, has not generated consistent revenues from its operations to date and is not currently profitable.

- If the group is unable to maintain or increase originations through the platform or if existing customers or IM funders do not continue to participate on the platform, its business, results of operations, financial condition or prospects will be adversely affected.

- If the scoring models and processes that the group uses contain errors or are otherwise ineffective, or if customer data is incorrect or becomes unavailable, the group’s business may suffer.

- The group has built value into its business through the TradeFlow Acquisition.

- Any failure of the platform or the group's future platforms, software and technology infrastructure could materially adversely affect its business, results of operations, financial condition or prospects.

- The group's ability to protect the confidential information of its customers and IM funders may be adversely affected by cyber-attacks, computer viruses, physical or electronic break-ins or similar disruptions or faults with its systems.

- The group may be unable to retain or hire appropriately skilled personnel required to support its operations.

- The group’s success and future growth depend significantly on its successful marketing efforts, increasing its brand awareness, and its ability to attract new IM funders and customers.

- The supply chain financing market is competitive and evolving.

- Unfavourable general economic conditions may have a negative impact on the results of operations, financial condition and prospects of the group.

- The group may need additional financial resources to develop the platform for future success.

- Uncertainties in the interpretation or application of, or changes in, IFRS or local GAAP could adversely affect the "derecognition treatment" for customers that comply with IFRS or local GAAP and accordingly reduce customers’ or IM funders’ participation on the platform.

- The ownership and use of intellectual property by the group may be challenged by third parties or otherwise disputed.

- Shareholders’ interests may be diluted by future issues of Secondary Admission Shares and Further Admission Shares.

- Prospective investors and Shareholders should be aware that there may be possible volatility in the price of the Ordinary Shares.

- A Standard Listing affords Shareholders a lower level of regulatory protection than a Premium Listing.

- Dividend payments on the Ordinary Shares are not guaranteed, and the Company does not intend to pay dividends for the foreseeable future.

- The group is subject to complex taxation in multiple jurisdictions, which often requires subjective interpretation and determinations. As a result, the group could be subject to additional tax risks attributable to previous assessment periods.

- Changes in tax law or the interpretation of tax law, or the expansion of the group’s business into jurisdictions with less favourable tax regimes, could increase the group’s effective tax rate and in turn adversely affect its business, results of operations, financial condition and prospects.

- There can be no assurance that the company will be able to make returns to Shareholders in a tax-efficient manner.

How much can I expect to make from an investment in the company?

What's the expected return of an investment in the company?

We estimate that the expected return of an investment in the company over the next five years is negative 24%. In other words, an £1,000 investment in the company is expected to return £760 in five years time. The assumptions used to estimate the return figure can be found in the table below.

Assuming that a suitable return level over five years is 10% per year and Supply@ME Capital achieves its expected return level (of negative 24%), then an investment in the company is considered to be an 'unsuitable' one.

What are the assumptions used to estimate the return?

| Description | Value | Commentary |

|---|---|---|

| Which valuation model do you want to use? | Discounted cash flow | There are two main approaches to estimate the value of an investment:

Research suggests that in terms of estimating the expected return of an investment over a period of 12-months or more, the approach that is more accurate is the discounted cash flow approach[17], so that's the approach that we suggest to use here; nevertheless, for completeness purposes, separately, the valuation of the company is also estimated using the using the relative valuation approach (the valuation based on the relative approach can be found in the appendix of this report). Supply@ME Capital has never paid cash dividends, and on 7th February 2022, it said that it currently does not anticipate paying any cash dividends in the foreseeable future. Accordingly, we suggest using the free cash flow valuation method (rather than the dividend discount model). |

| Which financial forecasts to use? | Proactive Investors | The only available long-term forecasts (i.e. >15 years) are the ones that are supplied by us (the forecasts can be found in the financials section of this report), so we suggests using those. |

Growth stage 2

| ||

| Discount rate (%) | 15% | There are two key risk parameters for a firm that need to be estimated: its cost of equity and its cost of debt. A key way to estimate the cost of equity is by looking at the beta (or betas) of the company in question, the cost of debt from a measure of default risk (an actual or synthetic rating) and apply the market value weights for debt and equity to come up with the cost of capital. |

| Probability of success (%) | 90% | Research suggests that a suitable rate for a company in this growth stage (i.e. stage 2) is 90%. |

Growth stage 3

| ||

| Discount rate (%) | 10% | There are two key risk parameters for a firm that need to be estimated: its cost of equity and its cost of debt. A key way to estimate the cost of equity is by looking at the beta (or betas) of the company in question, the cost of debt from a measure of default risk (an actual or synthetic rating) and apply the market value weights for debt and equity to come up with the cost of capital. |

| Probability of success (%) | 100% | Research suggests that a suitable rate for a company in this growth stage (i.e. stage 3) is 100%. |

Growth stage 4

| ||

| Discount rate (%) | 10% | There are two key risk parameters for a firm that need to be estimated: its cost of equity and its cost of debt. A key way to estimate the cost of equity is by looking at the beta (or betas) of the company in question, the cost of debt from a measure of default risk (an actual or synthetic rating) and apply the market value weights for debt and equity to come up with the cost of capital. |

| Probability of success (%) | 100% | Research suggests that a suitable rate for a company in this growth stage (i.e. stage 4) is 100%. |

Other key inputs

| ||

| What's the current value of the company? | $950.54 billion | As at 5th June 2022, the current value of the Supply@Me Capital company is $950.54 billion. |

| Which time period do you want to use to estimate the expected return? | Between now and five years time | Research suggests that following a market crash, the average amount of time it takes for the price of a stock market to return to its pre-crash level (i.e. the recovery period) is at least three years.[18] Accordingly, we suggest that to account for general market cyclicity, it's best to estimate the expected return of the company between now and five years time. |

Sensitive analysis

The main inputs that result in the greatest change in the expected return of the Supply@Me Capital investment are, in order of importance (from highest to lowest):

- The size of the total addressable market (the default size is $3.0 trillion);

- Supply@Me Capital peak market share (the default share is 10%); and

- The discount rate (the default time-weighted average rate is 10%).

The impact of a 50% change in those main inputs to the expected return of the Supply@ME Capital investment is shown in the table below.

| Main input | 50% worse | Unchanged | 50% better |

|---|---|---|---|

| The size of the total addressable market | N/A | (24%) | N/A |

| Supply@ME Capital peak market share | N/A | (24%) | N/A |

| The discount rate | N/A | (24%) | N/A |

Appendix

Relative valuation approach

As noted earlier in this report, research suggests that in terms of estimating the expected return of an investment over a period of 12-months or more, the approach that is more accurate is the discounted cash flow approach, so that's the approach that we suggest using to determine the estimated value of the company (the valuation based on the discounted cash flow approach can be found in the valuation section of this report); nevertheless, for completeness purposes, separately, the valuation of the company is also estimated using the relative valuation approach.

What's the expected return of an investment in the company using the relative valuation approach?

Accordingly, We estimate that the expected return of an investment in Supply@ME Capital over the next five years is 4.4x. In other words, an £1,000 investment in the company is expected to return £4,400 in five years time. The assumptions used to estimate the return figure can be found in the table below.

Assuming that a suitable return level over five years is 10% per year and Supply@ME Capital achieves its expected return level (of 4.4x), then an investment in the company is considered to be a 'suitable' one.

What are the assumptions used to estimate the return figure?

| Description | Value | Commentary |

|---|---|---|

| Which type of multiple do you want to use? | Growth-adjusted EV/sales | For the numerator, we believe that to account for the different financial leverage levels of its peers, it's best to use enterprise value (EV), rather than price. For the denominator, we believe that because it expects Supply@ME Capital to reinvest almost all of its revenue back into the business over the five year forecast period and therefore its earnings are expected to be abnormally low over the period, it's best to use sales. Accordingly, we suggest valuing its company using the EV/sales ratio. However, we feel that to take into account the different business lifecycle stages of its peers, the most suitable valuation multiple to use is the growth-adjusted EV/sales multiple[Note 3], rather than the EV/sales multiple. |

| In regards to the growth-adjusted EV/sales multiple, for the sales figure, which year to you want to use? | Year 1 | Research suggests that when using the relative valuation approach, it's best to use a time period of 12 months or less. Accordingly, for the sales figure, we suggest using Year 1. |

| In regards to the growth-adjusted EV/sales multiple, for the sales growth figure, which year(s) do you want to use? | Year 2 to 4, from now | We suggest that for the sales growth figure, it's best to use Year 2 to 4. |

| In regards to the growth-adjusted EV/sales multiple, what multiple figure do you want to use? | 100x | In our view, Supply@ME Capital's closest peer is Apple, Inc. Apple, Inc trades on a multiple of 100x. |

| Which financial forecasts to use? | Proactive Investors | The only available forecasts are the ones that are supplied by us (the forecasts can be found in the financials section of this report), so we suggest using those. |

| What's the current value of the company? | $688 billion | As at 21st May 2022, the current value of its company at $688 billion. |

| Which time period do you want to use to estimate the expected return? | Between now and one year time | Research suggests that when using the relative valuation approach, it's best to estimate the expected return of the company between now and one year time. |

Sensitive analysis

The two main inputs that result in the greatest change in the expected return of the Supply@ME Capital investment are, in order of importance (from highest to lowest):

- The growth-adjusted EV/sales multiple (the default multiple is 50x); and

- The Year-one sales forecast (the default forecast is $1 million); and

- The Year 2 to 4 sales growth forecast (the default forecast is 300%)

The impact of a 10% change in those main inputs to the expected return of the Supply@ME Capital investment is shown in the table below.

| Main input | 10% worse | Unchanged | 10% better |

|---|---|---|---|

| The growth-adjusted EV/sales multiple | |||

| The Year-one sales forecast | |||

| The Year 2 to Year 4 sales growth forecast |

Key principal activities

The Platform

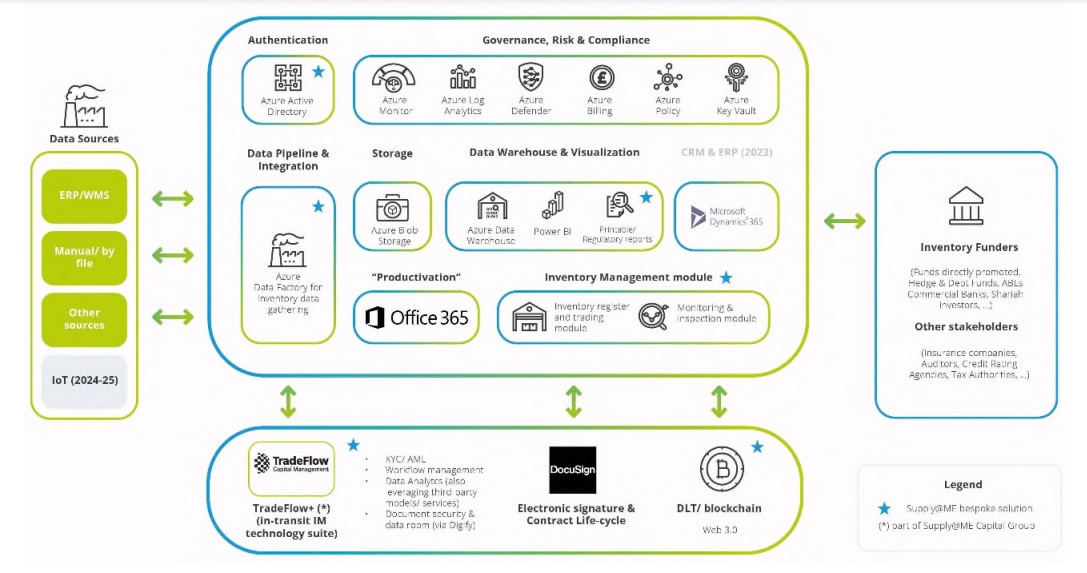

The group is a fintech company providing a inventory monetisation (IM) service to companies in a wide range of industrial sectors utilising the platform, which comprises a unique combination of software modules, exponential technology components (such as AI, IoT) and Blockchain), dedicated legal and accounting frameworks and business rules/methodologies delivered via a hybrid ICT architecture.

Specifically, the ICT architecture envisages the use of two cloud environments (Microsoft Azure for warehoused goods monetisation and Amazon Web Services for the in-transit model delivered by TradeFlow) plus an external integration with distributed ledger frameworks.

Diagrammatic illustration of the Platform:

Source: 2021 Annual Report

The stakeholders of the platform are:

- the Fund, via dedicated compartments and their StockCos, the trading vehicles who purchase inventory from corporate clients;

- potential IM funders, who can invest in the Fund and/or act as direct lenders to the StockCos;

- TradeFlow acting as investment advisory company of the Fund;

- corporate clients, as commercial counterparties of the StockCos or directly of the Fund; or

- banks, as white-label users of the Platform as a service (underpinning their inventory based and/or backed financial products directly provided by the banks to their clients).

The platform’s road-map envisages that data sources have a key role for the platform, triggering the value-added service provided by the group (whether inventory data analysis or IM provided by the Fund. Accordingly, data ingestion services have a critical role in the overall platform operations. Additionally, the inventory register and trading modules are able to produce the data analysis and support the creation of the security package in favour of the IM funders involved in each IM deal.

The monitoring component of the platform is constructed by business rules (which support the creation of specific key risk and performance indicators) and are expected to be underpinned by software modules able to enable the user to visualise early warnings, trigger inspections (to report digitally) and track the action plan/remediation plan agreed with the corporate client. The Platform’s road-map further envisages the adoption of IoT frameworks in order to improve the effectiveness and the efficiency of the monitoring and inspections activities.

TradeFlow uses a dedicated suite (TradeFlow+) made of multiple software modules reflecting the expertise of the team in the trade finance space, delivering a unique non-credit approach aimed at monetising inventory in-transit (import/export transactions where the buyer is supported to optimise its supply chain relationship).

The revenue model

Over recent months, the group has clarified and fine-tuned its overall business model, distinguishing the pure FinTech business (the platform being the group's people and software) from the inventory funding structure. In this regard:

- the platform has, by definition, an intrinsic value and accordingly can also be used by other operators (such as banks or other debt funders) to improve inventory backed or based facilities. The company considers it to be an enabler of each transaction. For this reason, the group officially launched its white-label initiative at the end of August 2020, invested further time in upgrading ICT architecture, selected and started new tech streams, while leveraging and understanding the components used by TradeFlow Capital within its TradeFlow+ system; and

- the areas of improvement suggested by IM funders in the last year regarding the introduction of an equity (first loss) line in the capital structure of each IM transaction was addressed with the launch of the Fund compartments, which can work as an equity provider and/or on a standalone basis (the Fund able to deliver by itself an IM transaction).

As such, the group is now focused on establishing and growing the following active, and future, revenue streams:

- "Captive" IM platform servicing ("C.IM"): revenue generated through the use of the platform to facilitate IM transactions performed by the Fund and its IM funders. This revenue is generated by the group’s operating subsidiaries, and in the future is expected to be supplemented by Tijara Pte Limited, a technology subsidiary company of TradeFlow. Revenue is expected to be earned in relation to the following activities:

- origination and due diligence (pre-IM); and

- monitoring, controlling and reporting (post-IM).

During the year ended 31 December 2021, the group recognised £0.3m of C.IM revenue relating to due diligence fees. During the six month interim period ended 30 June 2022, the C.IM revenue relating to due diligence fees was nil. When fully delivered, this stream is expected to generate revenues of approximately 1-3% of the gross value of the inventories monetised (purchase price plus VAT).

- "White-label" IM platform servicing ("WL.IM"): revenue to be generated through the use of the platform by third parties who choose to employ the self-funding model. When delivered, this stream is expected to generate recurring software-as-a-service revenues of approximately 0.5-1.5% of the value of each IM transaction (the amount of funding provided). No WL.IM revenue was recognised by the group during the year ended 31 December 2021 or during the six month interim period ended 30 June 2022.

- Investment Advisory ("IA"): the revenue stream currently being generated by TradeFlow in its capacity as investment advisor to its well-established funds, as well as its anticipated role as investment advisor to the Fund going forward. This stream is expected to generate recurring revenues of approximately 1.25% of Assets Under Management for which TradeFlow acts as advisor. Additionally, TradeFlow could receive a further performance incentive fee of up to 15% of the profits generated by the Fund, based on performance. During the year ended 31 December 2021, the group recognised £0.2m of IA revenue, representing TradeFlow’s addition to the group’s revenue from 1st July to 31st December 2021. During the six month interim period ended 30th June 2022, the group recognised £0.2m of IA revenue.

Operational and principal activities

Recently introduced significant new products or services

Since 31th December 2021 (being the date to which the last published audited financial statements for the company and the group were made up), the group announced the execution of a strategic alliance agreement on 28th June 2022 (the "VeChain Agreement") with the VeChain Foundation ("VeChain"), a blockchain enterprise service provider focused on supply chain and sustainability, to fund the first inaugural IM transaction and kick off the "Web3" stream.

The objective of the VeChain Agreement is to create a sustainable Web3 environment that will allow direct participation in the IM journey combining traditional finance with the blockchain space. According to Messari research, the top 100 digital assets in circulation capitalise over US$1.2 trillion, of which approximately 60% are currencies, like Bitcoin, and stablecoins, like Tether.

The VeChain Agreement has two phases, both in terms of investment opportunities and technology development.

In Phase One, a proof-of-concept real transaction involving a client company already selected by SYME from its existing Italian portfolio, with the VeChain Foundation serving as provider of its VeChain Thor blockchain and non-fungible token ("NFT") investor.

Following the successful completion of the first transaction and an assessment of the innovative process designed to link digital assets to the real economy, Phase Two will build up an "IM Platform 3.0" with an expected roadmap of Web3 features, including the issuance of NFTs, digital ownership and B2B marketplaces, decentralised finance (DEFI) and, overall, a governance protocol. For this phase, to be completed by end of December 2022, it’s expected the IM transactions will be also funded by further multiple liquidity providers (crypto asset managers and direct IM investors through liquidity pools partnerships).

The commitment budgeted by VeChain within the VeChain Agreement to directly subscribe the Inventory (NFT-based) Monetisation Transactions is up to US$10m, of which approximately US$1.6m immediately releasable to fund the available eligible inventory of the first Italian client selected and the rest, during the Phase Two, for one or more further client companies, also including the current UK portfolio.

Recent commercial developments

On 12th September 2022, the company announced the execution of the group's first IM transaction in connection with Phase One of the VeChain Agreement. The client company to this inaugural IM transaction is a well-established business with significant market presence in Europe (mainly in Italy), Africa and the United States. The client company is involved in the design and manufacture of industrial and specialised vehicles as well as electronic systems, electrical wiring, and other components.

The inaugural IM transaction has been structured as follows:

- a StockCo, an overview of which was given in the SYME Business Model Canvas in the 2021 Annual Report, entered into the commercial contractual package, with a duration of three years, with the client company to execute the inaugural IM transaction. The total value of the initial warehoused goods to be monetised is approximately €1.6m;

- with reference to the fully owned SYME subsidiaries:

- Supply@ME Italy, acting as originator and servicer, signed an operating agreement with StockCo which includes an annual inventory servicing fee and, additionally, will charge the client company an up-front origination fee;

- NewCoTech, owner of the IM intellectual property rights and acting as platform provider, has signed a license agreement with the StockCo and will charge an annual platform fee. The platform will be used by the client company to upload inventory to be monetised (and, accordingly, minting the NFTs), integrate and transfer the Enterprise-Resource-Planning data to allow the necessary monitoring and inspection activities by the StockCo, supported by Supply@ME Italy; and

- StockCo, in turn, mints NFTs to be subscribed by VeChain under the VeChain Agreement. Each NFT represents a basket of rights over the inventory, including the opportunity to achieve monthly returns generated by the inventory trading activities performed by the StockCo and the right of the NFT holder, as ultimate owner of the goods, to take possession of the physical goods if certain conditions are met.

Major shareholders

The table below shows those who hold 3% or more of the company's share capital, as of 14th October 2022.

| Shareholder | Number of Ordinary Shares | Percentage of the issued share capital |

|---|---|---|

| The AvantGarde Group S.p.A. | 12,742,513,009 | 22.51% |

| Venus Capital S.A. | 7,900,000,000 | 13,95% |

Note, the total number of issued share capital is as follows: 56,617,688,143 ordinary shares.

Other

Dividends

To date, the company has not declared or paid any dividends on the Ordinary Shares. The Company’s current intention is to retain earnings, if any, to finance the operation and expansion of the Group’s business, and does not expect to declare or pay any cash dividends in the foreseeable future.

Interesting/useful extract/information

Trade finance is the backbone of international trade for entities ranging from a small businesses to multi-national corporations. An estimated 80 percent of world trade relies on this form of finance (WTO, 2017). Despite its systemic importance and rapid growth, data availability is only partial. During the 2008 financial crisis, policy makers, notably the G20 recognized that the absence of comprehensive trade finance data posed a significant hurdle for policy-makers to make informed, timely decisions. This paper proposes a standalone dataset to reflect the scope, dynamic and recent innovations of the trade finance market to support macroeconomic policy analysis.

Blockchain and smart contracts are considered a “game changer technology that can transform trade finance processes.[19]

There is, therefore, a close relationship between a company’s management of supply chain activities and its financial performance.

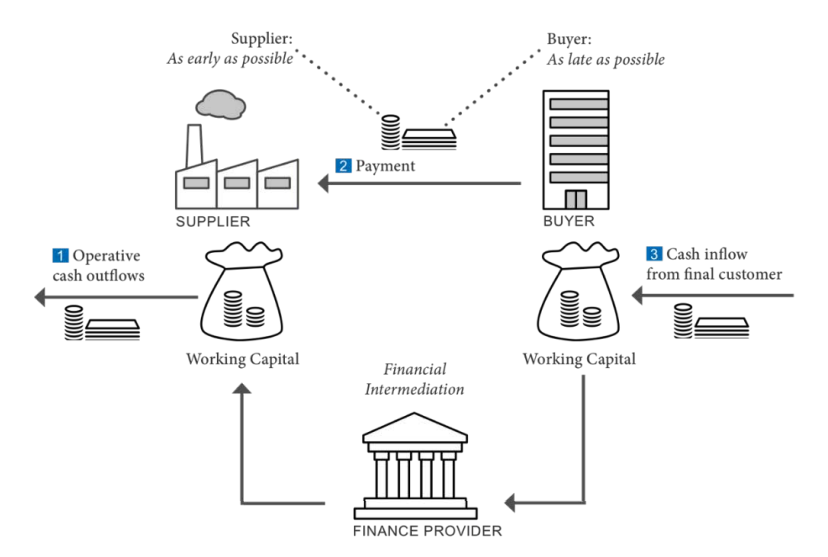

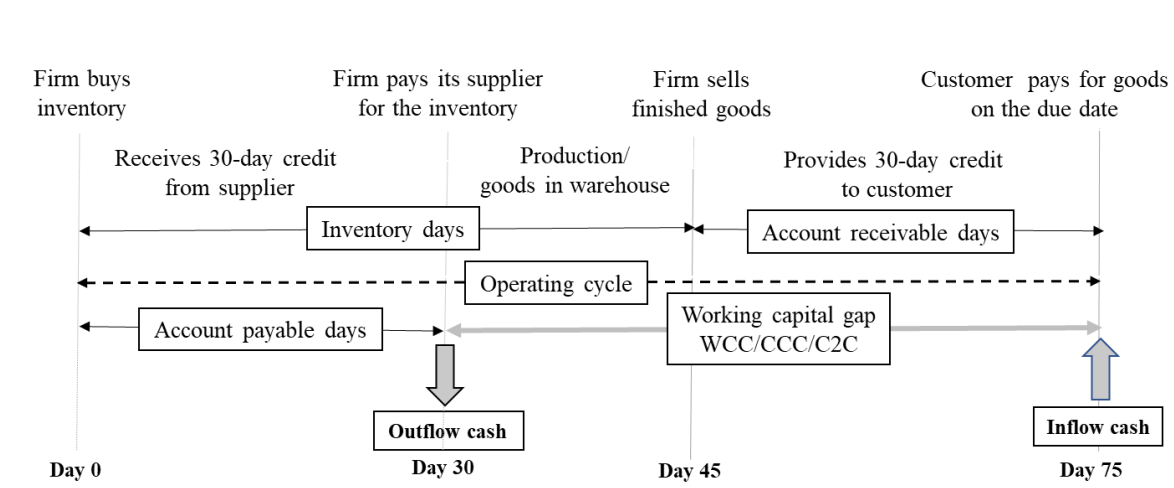

Working Capital is the Starting Point for Trade Financing

The working capital ratio (current assets/current liabilities) indicates whether a company has enough shortterm assets to cover its short-term debt. Balanced cash management in a business is essential because insufficient cash and no alternative funding means there are not enough funds to meet obligations such as buying raw materials or paying wages and overheads. Too much cash, on the other hand, means a company has idle funds for which it foregoes investment. Holding too much inventory has implications for the financial performance of a business in the form of costs for storage, handling, insurance, etc., and cash tied up that could be used otherwise. The right balance is a trade-off between liquidity versus profitability. As illustrated in the diagram below, suppliers need to get paid as early as possible, while buyers want to pay as late as possible. When the cash collection of suppliers slows down, suppliers have limited practical alternatives. They can extend the credit line or take out short-term debt with their local bank; they can use the accounts receivable as collateral to raise cash; or extend their payables. Depending on the size, location, and credit-worthiness of the suppliers, only limited options may be available—if alternative financing is not feasible, they may need to slow down their business. The underlying friction between suppliers’ and buyers’ objectives was severely magnified during the 2008 financial crisis.

Source: IMF Staff.

Micro, small and medium-sized enterprises, especially in developing countries, are often faced with a mixture of structural constraints and are required to set aside large collaterals against trade loans or pay high fees. Long waiting times, the combination of costs with high coordination efforts, foreign currency risks and time restrictions, make L/Cs cumbersome especially for this group of enterprises. The availability of trade finance often depends on the extent to which the local banking sector is developed and internationally networked.[20]

L/Cs and other short-term pre-shipment trade loans and guarantees ensure payment for suppliers, on time and for the correct amount, before the actual change of ownership occurs and financial assets and liabilities are created. This is in contrast to trade credit and advances, when financial instruments are created concurrently with the change of ownership. Once the conditions of the L/C are met, the supplier receives payment, and the buyer receives the documents needed to claim ownership.

Rejected trade finance requests from SMEs, and the global financial and economic crisis, exposed an incomplete trade finance market with demand exceeding supply, alarming new businesses, market observants and political leaders.[21]

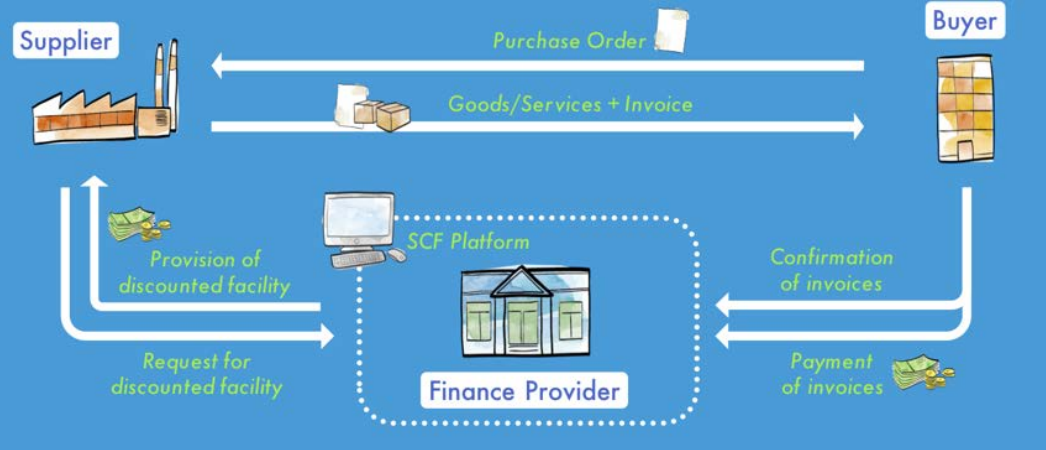

SCF solutions refer to instruments allowing the largest company of a supply chain to use its superior credit rating to give its lower-rated suppliers access to financing at more favourable rates than they would obtain otherwise. Benefits include lengthening payment terms for buyers and shortening them for suppliers, thus improving working capital for both. New SCF solutions are offered by SCF providers (Fintechs) or directly by banks that have SCF in their service portfolio.

SCF is enabled through integrated technology platforms – SCF portals– that make it possible to extend payment terms to buyers while accelerating payment to suppliers (see Figure 3). Suppliers of all sizes upload their invoices directly to the portal or send their invoice using specific accounting software. The buyer approves the invoice for early payment by the SCF provider and the full invoice amount less a financing fee is transferred to the supplier’s bank account. At maturity of the invoice period (with or without extension), the buyer will pay the due amount directly to the finance provider (if the supplier has sold the invoice) or to the supplier’s bank account (if the supplier has not sold the invoice).

Programs are connected with multi-funding sources to deal with multiple currencies and jurisdictions as well as to work with non-investment-grade or unrated companies. Globally operating banks see SCF as an important new area of their activity and focal point of current research and development. It is expected that the Internet of Things (IoT) and smart contracts will allow real-time tracking of goods which could become a powerful big data source for real-time data.

In developing economies, supply chain financing could enable financial intermediaries to provide funding to SMEs without having to accept their risk, basing the risk assessment on the creditworthiness of the onboarding buyers. The African Development Bank estimated that Africa has an unmet demand for trade finance of more than US$90bn and Asia of $425bn annually.[22]

Source: IMF Staff.

Special cases of SCF are (i) loan or advances against inventory – an asset-based financing instrument where the finance provider obtains title over the goods as collateral (e.g., Finetrading); (ii) inventory repurchase (repo) agreements, or buy-back agreements where the buyer/supplier temporarily “sells” its inventory to a financing entity, and “buys’ it back after a predetermined time; however, the inventory stays on the balance sheet and the funds received are recorded as liability until the repurchase takes place within the pre-agreed upon period.

Finetrading, in contrast, is not considered a financial transaction because the Finetrader acquires the goods and not the claim. Finetrading combines ‘Finance’ and ‘Trading’ especially by SMEs. The Finetrader takes ownership and pre-finances the goods on behalf of the buyer for a defined financing period. For the buyer, the benefits are reduced inventory and improved working capital, while the supplier gets paid immediately. Finetrading is a trade finance tool typically provided by intermediaries other than banks.

Secondary markets

Because of the difficulties SMEs often face with obtaining credit through regular channels, securitization (in addition to SCF) could enhance the financial base by enabling risk-transfer from banks to a wider pool of investors beyond the banking sector. Depending on the size of the market, SCF and securitization may also contribute to a decrease in financial stability.

Currently, there is no comprehensive global dataset separately covering trade finance statistics.

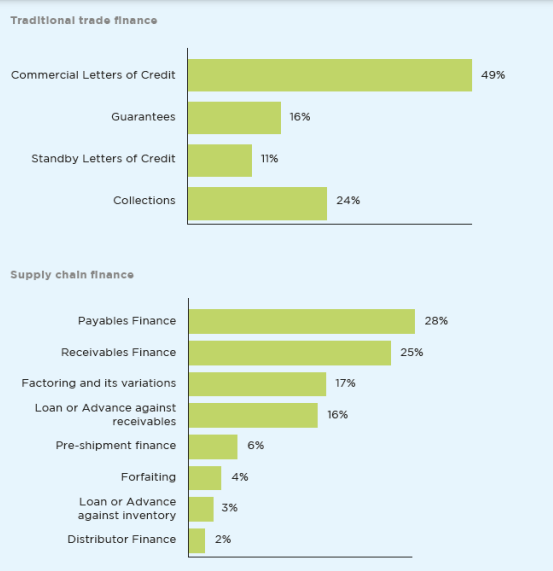

trade finance encompasses a wider range of instruments at the financiers’ disposal (see Figure 4)—these financial instruments require additional breakdowns to the standard financial account classifications and components.

Traditional L/Cs are not included in the macroeconomic statistics because they are considered contingent instruments, therefore off-balance sheet and not recorded as financial assets. Therefore, extensions are required to the current macro-statistical frameworks to facilitate an accurate measurement of domestic and cross-border trade finance.

Most Used Instruments in Traditional Trade and Supply Chain Finance

Source: Source: ICC Global Survey on Trade Finance 2018

The G20 acknowledged that international statistics produce insufficient data on trade finance and asked to “coordinate and establish a comprehensive and regular collection of trade credit in a systematic fashion.”

To fill the data gap during the latest global financial crisis, the IMF and the Bankers' Association for Finance and Trade (BAFT) conducted four ad hoc surveys of banks between 2008 and 2010 on volume, prices, and drivers of trade finance.[23]

New Supply Chain Finance (SCF) Instruments

SCF Definition Established by the Global Supply Chain Finance (GSCF) Forum

Supply Chain Finance is defined as the use of financing and risk mitigation practices and techniques to optimize the management of the working capital and liquidity invested in supply chain processes and transactions.

SCF is typically applied to open account trade and is triggered by supply chain events. Visibility of underlying trade flows by the finance provider(s) is a necessary component of such financing arrangements which can be enabled by a technology platform. […]

[The buyers and sellers] often have objectives to improve supply chain stability, liquidity, financial performance, risk management, and balance sheet efficiency. SCF is not a static concept but is an evolving set of practices.

Accounts Receivable Centric

SCF Category Accounts or trade receivables refer to the outstanding invoices that a supplier has vis-à-vis the buyer of its goods and services. Receivables are recorded separately on the balance sheet as short-term claims. Using a receivables purchase program, the supplier sells all or parts of these outstanding claims to a financial intermediary or SCF service provider which takes full legal and economic ownership (and not just a security interest in the collateral); in return, it provides the supplier with working capital in form of advance payments less the financial service charge (called discount), reducing the days sales outstanding (DSO) and providing much needed liquidity the company can work with.

The following three techniques on the market are seller (supplier)-led programs.

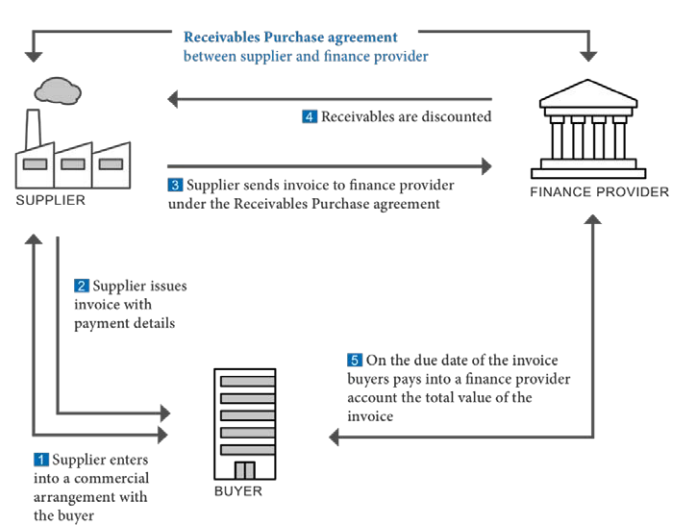

(1) Receivables Discounting (Annex Figure 1) allows suppliers with outstanding short-term invoices mostly vis-à-vis multiple buyers to sell their receivables to a financial provider at a discount. This instrument is usually reserved to investment-grade suppliers that have a minimum credit rating. This allows the finance provider to offer this program on a full or partly “without recourse”[24] basis; i.e., the supplier can remove the accounts receivables'' completely or partly from its balance sheet, and the finance provider bears the risk in case the buyers fail to perform their payments. A trade credit insurance can limit the risk exposure of the finance provider. This financing transaction between the supplier and a finance provider can be made with or without the knowledge of the buyers; and depending on the situation in some cases, the buyers may be asked to validate their accounts payables.

Source: IMF Staff.

At maturity, the buyers pay the amounts of the invoices into the bank account (i) of the supplier, with limited access rights of the supplier; (ii) of the finance provider (the finance provider does not have to be a bank); or (iii) of the supplier without restriction, adding an additional element of risk for the finance provider.

The buyer benefits from extended credit terms in a stable supply chain environment. The supplier profits from increased short-term liquidity. And the finance provider provides services in a relatively stable non-speculative financial environment.

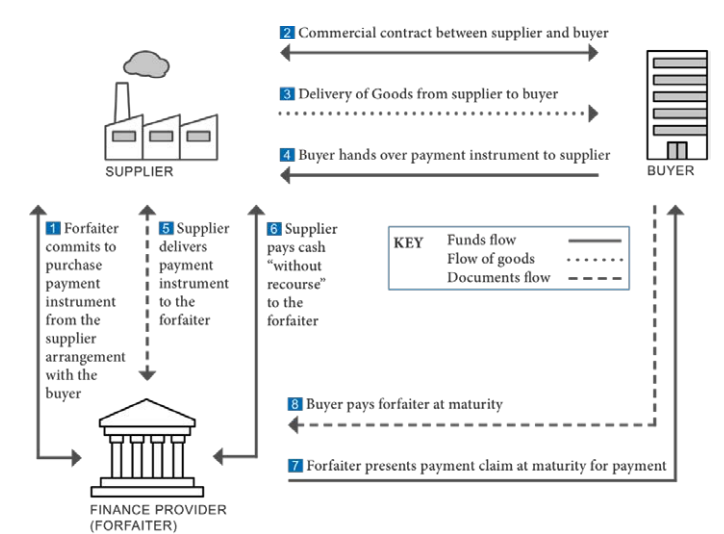

(2) Forfaiting (Annex Figure 2) is an export-oriented form of supply chain finance where a forfaiter (finance provider) purchases from the supplier, without recourse, future payment obligations and trades these as negotiable debt instruments in the form of bills of exchange, promissory notes, or Letters of Credit (L/Cs) on the secondary forfaiting market. These payment instruments are legally independent from the underlying trade and require a guarantee by a third party (normally the buyer’s bank).

Source: IMF Staff.

In the secondary market, forfaiters deal with financial investors. In the primary market, the supplier approaches the forfaiter before signing the contract with the buyer. The buyer obtains a bank guarantee and provides the documents that the supplier requires to complete the forfaiting. After receiving 100 percent cash payment against delivery of the payment (debt) obligation, the supplier has no further interest in the transaction, because the forfaiter must collect the future payments plus forfaiting costs (included in the invoice price) via the guarantor from the buyer. Forfaiting involves mostly medium-to-long-term maturities, and is most commonly used in large, international sales of capital goods.

Forfaiting helps suppliers trade with buyers of countries with high levels of risks, and obtain a competitive advantage by being able to extend credit terms to their customers. While the without-recourse-sale eliminates all risks for the supplier, the forfaiter charges for credit risks as well as for covering the political, commercial, and transfer risk related to the importing country, which is also linked to the length of the loan, the currency of transaction, and the repayment structure. The costs are higher than commercial bank financing, but more cost effective than traditional trade finance tools. Forfaiting is only used in international trade financing.

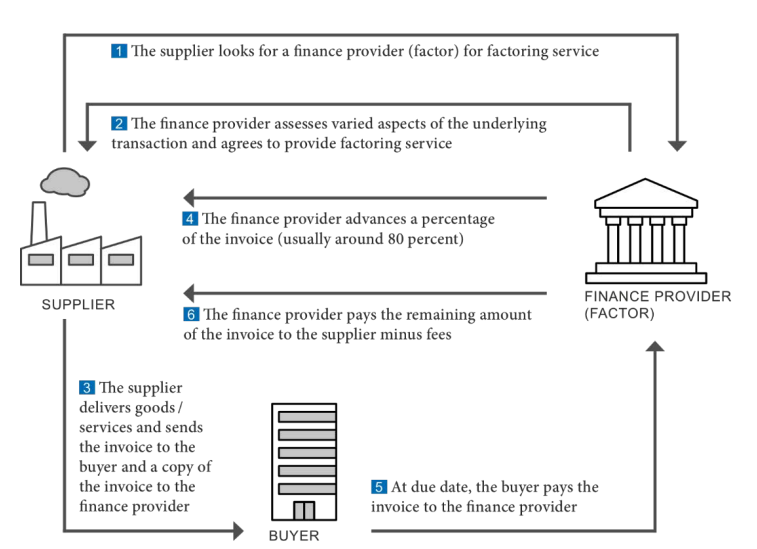

(3) Factoring (Annex Figure 3) targets the domestic and international market, whereby the latter often includes two “factors,” one in each country. The suppliers, often SMEs, receive around 80 percent of the invoice value from the factor as advance payment, and a remaining, but discounted, value when payment is due by the buyer. The fees and discounts are borne by the supplier in return for the factor’s services of advancing funds and managing the collecting of the receivables from the buyer. Because factoring is available with and without recourse, depending on the circumstances in the market, the factoring institution may add a credit insurance. Factoring provides suppliers with working capital, albeit discounted, allowing them to continue trading, while the factor receives margins from rendering the service.

Source: IMF Staff.

Asset-based financing linked to the physical supply chain is not a new concept. There are a variety of traditional techniques for accessing finance both pre- and post-shipment. However, traditional factoring is often not fit for purpose for small businesses, as it typically entails long-term, complex contracts with fixed volumes.[25] The innovations with SCF are the automated business processes and e-invoicing tools that are based on a central technology platform simultaneously accessed by buyers, sellers, and SCF providers.[26]

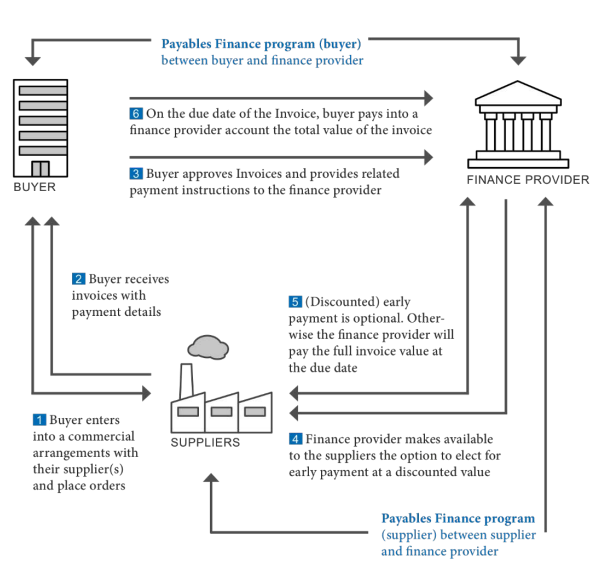

(4) Reverse Factoring, also known as Approved Payables Finance,[27] is a buyer-led and arranged financing program for designated suppliers in the supply chain (Annex Figure 4). The buyer’s creditworthiness allows the supplier to receive an early discounted payment for the accounts receivables, typically without recourse. The buyer will later pay the due amount directly to the finance provider. Buyers can be large and medium-sized and at times even near non-investment grade (given, an established buyer-finance provider relationship exists); however, buyers only arrange the financing, they are not part of the financing transaction. As with previous cases, the assets are changing ownership from the suppliers to the financial intermediary. The early financing is for 100 percent of the receivables less a discount, which is lower than with conventional trade financing. As before, the buyer receives an extended term for payment in a secured supply chain environment.

Source: IMF Staff.

(4a) Dynamic Discounting is a variation to (4), where buyers use their own funds in to decide how and when to pay their suppliers in exchange for a discount on the purchased goods. The earlier the payment, the larger the discount. The buyers can use their own access liquidity to generate additional income, while the supplier can optimize the days outstanding and the working capital.

Dynamic discounting is a typical example where Fintech companies[28] entered the market as providers of web-based platforms that allow both parties to upload, view, and approve invoices for early payment. For the buyers, there is no additional cost; the suppliers are charged a fee once they request early payment of the approved invoices.

Overall, in this category of Accounts Receivable Financing the financial claims move from the suppliers’ books to the SCF providers (the service provider or directly to the finance provider); hence, no new financial debt is created in the books of the suppliers for receiving early payment, in return for new liquidity. On the creditor side, SCF programs[29] can be self-funded by the buyers, or composed of a mixed program where financing is shared by the buyers, capital markets, and financial institutions.

Loan/Advance based SCF category

The second SCF category is based on loans and advances, where financing is usually provided in return for rights to a collateral, and the loan is recorded as a liability in the beneficiaries’ balance sheet.

(5) The new edge to an existing instrument called Distributor Financing (or Channel Financing) is that large Multinational corporations [MNCs (as suppliers)] are using this instrument increasingly for expanding into emerging markets. The MNCs support the financing of a geographically important (network of) established distributors against their retail inventory, and the distributors repay their debt once the inventory is sold. Although the finance provider (e.g., local bank) is providing the funds and taking on the risks, often MNCs subsidize the financing by absorbing part of the interest margins or engaging in other forms of risk-sharing arrangements, and through reputational support. MNCs directly benefit from their suppliers’ sales of goods to these distributors (buyers), and indirectly, because a sound supply chain allows end-customers to profit from products that can be delivered without delay. Distributor Financing has limited impact on MNCs balance sheets compared to foreign direct investment. Therefore, Distributor Financing can be an alternative to direct investment and preferred to establishing inventory-carrying subsidiaries abroad. Through the engagement of the MNCs, distributors profit from better loan prices and bridging liquidity gaps. The collateral for the finance providers is usually an assignment of rights over the inventory.